Embracing Sync Technology

Blasphemy. Heresy. How dare he write such a travesty? Is this how you feel at seeing the title? If so, calm down. I guarantee by the time you’re done reading this you will look at the sync button from a different perspective. Assuming you take the time to read this. I’ll admit it is long, but it is thorough. Unfortunately, the more close-minded and ignorant a person is, the less likely they’ll take the time to actually learn something. If you despise the sync button, then this article is for you. If you embrace the sync button, then you’ll gain some new ammo when you try to defend your position.

So what are we going to discuss? I’m going to start with three scenarios. Each scenario is designed to open your mind, get your mental juices flowing, and allow you to see this argument from a different perspective. We’ll then discuss the controversy surrounding the sync button and examine what beatmatching is and what it isn’t. We’ll start with the latter first. I’ll enhance your view of beatmatching by describing two different approaches to it. With that out of the way, I’ll explain the problems I have with beatmatching being taken so seriously. Of course, this always leads to misconceptions, so I’ll tackle those next. To tackle the first misconception, I’ll explain my experience with beatmatching both from a DJ perspective and from an audience perspective. From the audience side of things, I’ll explain the unfair comparison of DJs when it comes to beatmatching. Here we’ll examine different reasons why some DJs beatmatch better than others, and you’ll learn that it isn’t always a matter of skill.

Once you’ve gotten that far into it, you’ll have a greater understanding of how DJs are compared unfairly. The next section I take great pride in. I’ll explain three different methods of beatmatching, and what goes through the DJ’s mind for each method. Sound interesting? I’ll then ask the burning question: Why did you become a DJ? The answer to this question will ultimately determine where you stand on the issue, and hopefully cause you to show more respect towards others. I’ll then offer various reasons as to why you SHOULD use the sync button. If you’re still not convinced, I’ll list some problems that beatmatching gives rise to. I’ll point out how modern DJs who condemn beatmatching are hypocritical when you look at the history of where we come from. Then I’ll list some of the lame excuses DJs give as to why you should not use the Sync button, and the real reason they complain. Finally, I’ll ask the question targeted at all up-and-coming DJs: Should you learn to beatmatch?

Scenario 1

Imagine that when you were a child you loved trying new foods. You went to all the local restaurants and fast food joints in your area, and tried every exotic dish you came across. Eventually you exhausted all the local resources, and found the variety to be lacking. You decided to attend culinary arts school and then travel the world in search of the finest recipes and ingredients. Years later you returned with a book full of food items not offered by any of the local food establishments. You imported fruits, vegetables, herbs, and spices that most of the locals never even heard of. You took pride in knowing that all your food items were organic and none of the meat came from factory farms. Each dish you created was designed to offer a variety of sensations. The side dishes were meant to compliment one another. Each meal was a work of art. In the end, you offered the finest selection of dishes, the widest variety of tastes, and healthy food of the highest quality.

As time went on, you began to hear rumors that local restaurants were making fun of you. You discovered that you were being called a fake. As you looked into these rumors, you discovered the source. It turns out that because you used a blender to chop your vegetables, instead of doing it manually, you were considered a phony. Apparently, the competitors didn’t care about the quality of your food, the quality of your ingredients, the variety of meals you offered, or the rave reviews of those who experienced your meals first hand. They didn’t care about the time, research, and creativity that went into each meal. They simply focused on the fact that you automated one small piece of the process. Apparently, your competitors had their priorities mixed up. As absurd as this may sound, this is EXACTLY what is happening in the DJ scene.

Scenario 2

Imagine an individual who worked in a factory, and it was their job to transport a liquid from one building to another. They were given two options. They could carry the liquid in two one-gallon buckets, one for each hand; or they could operate a forklift and transport a skid carrying four one hundred-gallon barrels. Since they took the time to get their forklift license, the decision was easy. As they drove the forklift carrying four hundred gallons of this liquid, they drove past an individual carrying two buckets. The individual looked at the person in the forklift with disgust, and proceeded to say in a cocky tone, “I don’t need a forklift to transport liquid”. Which of these two individuals is doing more work? It depends on how you define the work. The person carrying the buckets is obviously doing more physical work, but the forklift driver will ultimately get more work done. The person carrying buckets focuses only on the physical aspect, and blindly misses the point that he is carrying much less and will get less work done in the end. To make matters worse, it turns out that the individual bragging about doing more physical work was actually too lazy to get his forklift license. He refused to study the safety manuals, refused to practice with an instructor, and refused to get up early on weekends to attend classes and take his test. Ironically, the lazy person ends up making more work for themselves. This is EXACTLY what is happening in the DJ scene.

Scenario 3

Okay, this is where things get weird, and I need you to stretch your imagination for this one. Imagine a world where DJs mixed on very small platforms. The platforms were so small, that you could only stand on one foot. Beginner DJs would spend countless hours building up their endurance and improving their balance. They would balance on one foot for 10 minutes, then 20, then 30, and eventually an hour. Once they could stand on one foot for an hour, they would get bookings at their local venues. Crowds would judge them on how much they swayed, or how perfectly still they stood. Unfortunately, being able to stand on one foot for that long didn’t make them a good DJ. It had noting to do with the quality of their music, it had nothing to do with the variety of their music, it had nothing to do with their ability to work the crowd or tell a story with their mix, it had nothing to do with how they timed their mixes, and it had nothing to do with how creative they were with fades, loops, effects, and EQing.

Then one year, someone had the bright idea to make the platforms bigger. DJs no longer had to stand on one foot. A new generation of DJs had no desire to learn the art of balancing on one foot. The older DJs were outraged since that had long been an initiation rite. They would complain that now anyone could be a DJ. They called the new generation lazy, and took pride in standing on one foot even when the platforms were big enough for both feet.

Now you just happen to be one of those older DJs from this world. At first, you thought the idea of standing on two feet was cheating and swore to never do it. Heck, you even had a reputation of doing entire sets on one toe! Then one day, you were mixing alone in your house, and with no one looking, you decided to give it a try. Suddenly, you felt this incredible feeling of relief. You found it was more comfortable, and surprisingly more fun. You also discovered that you could focus more on the things that really mattered like timing, layering, and just being creative overall. You realized that standing on one foot really had nothing to do with what was really important, and you realized just how stubborn and ignorant the older DJs were. You continued to mix on one foot when you spun out, but you couldn’t help feeling annoyed that you were being pressured into conforming to something outdated just to cater to ignorance. Finally, you decided to stand up for what was right and expose the prevailing ignorance. You never became a DJ for the purpose of standing on one foot, you became a DJ because you loved the music. As absurd as this scenario may sound, this is EXACTLY what is happening in the DJ scene.

The Controversy

For decades, a DJ was simply someone who found music and shared it with others. The more passionate an individual was about finding music, the better the quality. People would learn about music by tuning into the radio or attending local clubs. To remain inconspicuous, countries occupied by Nazi Germany would rely on DJs to replace large orchestras. It wasn’t until the 1970’s that beatmatching would become popular amongst disco club DJs, and it wasn’t until the 1980’s that electronic music would become popular in clubs. As time went on, beatmatching was taken more and more seriously for certain musical genres, and beatmatching would become a requirement for any respectable club DJ. Beatmatching would become an initiation rite, where new DJs would need to learn how to beatmatch before being allowed to mix at clubs and raves.

But just what is beatmatching? Let’s start by saying what it isn’t. Beatmatching has nothing to do with finding music. It has nothing to do with the act of learning about hot tunes and the effort of tracking them down. This means that beatmatching has nothing do with the quality of the music. Beatmatching has nothing to do with a DJ’s decision to mix up the emotion or the energy of their music. It has nothing to do with their decision to play modern tracks or classic tracks. In most cases, it has very little influence on their ability to mix different genres. This means that beatmatching has nothing to do with a DJ’s decision to mix a variety of music. Beatmatching has nothing to do with a DJ’s ability to read the crowd, work the crowd, or a tell a story with their set. Beatmatching has very little to do with a DJ’s timing. Beatmatching has nothing to do with whether a DJ decides to fade a track in or out, or whether they decide to do a quick cut instead. Beatmatching has nothing to do with a DJ’s use of effects, samples, loops, filters, or EQs. It has nothing to do with whether or not the tracks are in key with one another.

With all that said, what really is beatmatching? Beatmatching is a two step process. The first step involves adjusting the tempo of one track to that of another. The second step involves balancing the two tracks so they stay in unison with one another. Through this process, beatmatching allows DJs a way to melt one track into another. It creates a flow where audiences can get lost in the music. One thing to keep in mind is that it only works for certain genres of music. For this reason, many radio DJs and wedding DJs do not beatmatch.

While vinyl ruled supreme, beatmatching was a manual process. It required a DJ to listen closely, and it took a steady hand. It also took practice. Beatmatching is a skill that one must work at. When vinyl was dethroned by CDs, the process of beatmatching changed very little. It was still a manual process requiring the DJ to listen and adjust the pitch fader. As technology evolved, DJs began using laptops and digital files. These digital files could store tempo information, and soon the dreaded Sync button was born. By activating the Sync button, tempos would be automatically matched. The skill of beatmatching was replaced by a single button. Newer DJs no longer had to put the time and effort into learning how to beatmatch. Old school DJs were outraged. Now anyone could be a DJ, or so they would say.

There is something we need to make perfectly clear. The Sync button can beatmatch for you, but that is all it does. It does not find you music and it does not mix for you. Unfortunately, the term beatmatching is sometimes used to describe the style of DJing that involves beatmatching. To avoid confusion, I use the term beatmixing if I’m describing the style. If a person uses the term beatmatching to describe a style of DJing, and they learn that the Sync button can beatmatch for you, they then jump to the wrong conclusion that it can mix for you. As you’ve read just previously, there are many DJing aspects that beatmatching has nothing to do with.

Two Kinds of Beatmatching DJs

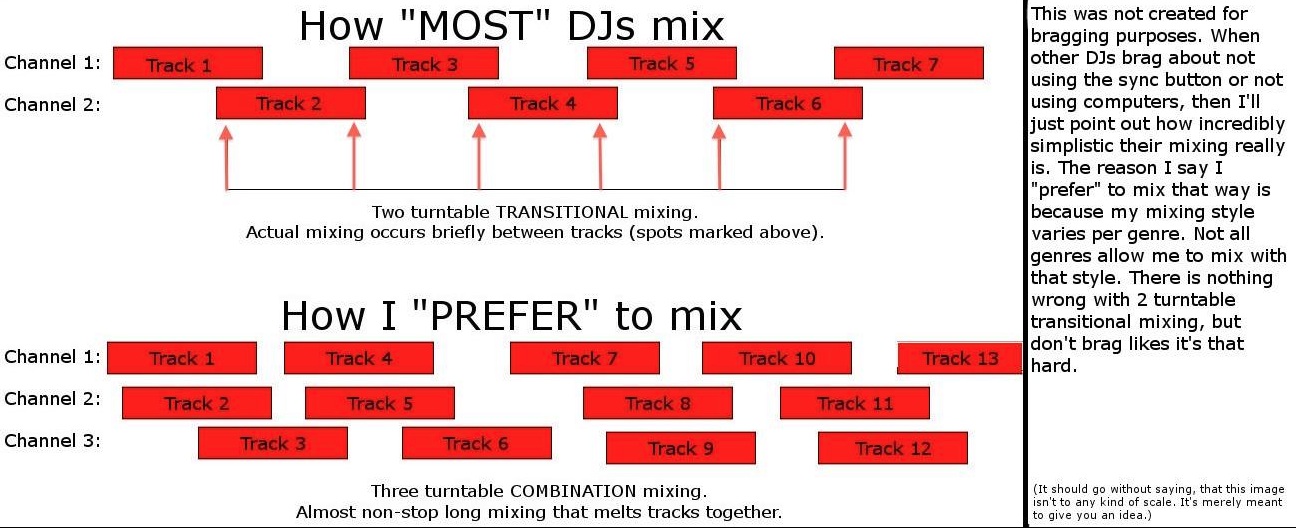

I would like to point out that there are two main reasons why DJs beatmatch. DJs beatmatch to transition between tracks, or they beatmatch to combine tracks. So we will describe these DJs as transitional DJs and combination DJs, and we’ll compare the two of them. These different approaches to beatmatching can ultimately influence a DJ’s opinion of the Sync controversy and the arguments for and against it.

Transitional DJs make up the largest percentage of club DJs. They use beatmatching to fade from one track into another. Their goal is to transition from track A to track B. On average, the transition may only last a minute. Let’s take a moment to do some math. If a DJ mixes for a minute between tracks, and averages 20 tracks per hour, then they’ve only done 19 minutes worth of mixing for their hour set. What did they do for the other 41 minutes of their set? Keep that in mind as you continue reading.

Combination DJs are much rarer. Their goal is to combine tracks. Most often these DJs are referred to as mash-up DJs, but that term usually refers to vocal mash-ups and quick mixing styles. Combination DJs can include techno DJs, tribal DJs, progressive DJs, and other styles where the tracks lack vocals and mixes are very long.

There is no black and white distinction between the two styles, it’s more a matter of percentages. A transitional DJ may combine a few tracks, but mostly transitions. A combination DJ may do a few transitions, but mostly combines. It can also be confusing when you consider that transitioning does involve tracks that are combined, and combination style DJs will eventually use those combinations to transition. What separates the two is the intended goal of the DJ and how long the mix occurs. A transitional DJ will mainly mix track B in near the end of track A, while a combination DJ will mix track B in shortly after track A begins. Transitional DJs are content with two turntables, while combination DJs tend to prefer a 3 turntable setup. Many combination DJs have embraced programs like Ableton, and as a result are more willing to embrace the Sync button. I consider myself to be a combination DJ, and I can’t stress enough the fact that most DJs are transitional. I also can’t stress enough that there is nothing wrong with being a transitional DJ.My Problem with Beatmatching

I have a problem with beatmatching. No, I do not have a problem being able to beatmatch. I have a problem with it being taken so seriously. Remember there are many aspects to DJing that beatmatching has nothing to do with. For decades prior to the 1970’s, DJs did not beatmatch. While beatmatching is definitely preferred, it is only one small part of the equation, and it is not the most important part. I believe that the quality of the music and variety are more important.

When I entered the rave scene in the 90’s, everyone was mixing vinyl, but that doesn’t mean we didn’t have our fair share of bad DJs. I’ve heard many DJs beatmatch flawlessly, but still suck. Let me repeat that, and let it sink in. A DJ can beatmatch flawlessly, and still suck. The reason they sucked is because their track selection was boring or cheesy, they lacked variety, and they had no clue how to work a crowd or tell a story. Many of these DJs would play a track the whole way through and just fade into the next. There was no creativity in their mix, and their timing was boring. In some cases the tracks would be out of key with one another, or in some cases two vocal tracks would clash with one another. If a DJ can beatmatch flawlessly and still suck, do you think the Sync button will change anything? So why do so many people say that “Now anyone can be a DJ” in response to the Sync button?

As I’ve mentioned earlier, being able to beatmatch was an initiation rite for DJs. Once a DJ learned how to beatmatch, they would be allowed to get booked at clubs and raves. The Sync button allows new DJs a way to bypass this initiation rite. The problem is not the Sync button. The problem is that being able to beatmatch should never have been an initiation rite. We should be judging DJs on the quality of their music, on the variety of their music, on their ability to work a crowd or tell a story, on their timing, and on their creativity with effects, faders, filers, EQs, samples, and loops. We should not be booking DJs just because they learned how to adjust tempos. That’s all beatmatching really is, just adjusting tempos. The Sync button is not the problem, it merely exploits a problem that was always present.

Before I even knew what beatmatching was, I wanted to be a DJ. For me, an underground DJ was someone who procured the finest selection of music regardless of how popular it was and shared that music with others. That was my goal for becoming a DJ, not to adjust tempos. Like most DJs, I have a love/hate relationship with beatmatching. Sometimes I enjoy it, and sometimes I find it annoying. I love mixing, but beatmatching is only a small part of the process. I started raving during the vinyl days where all DJs had to beatmatch. Since it was so common, I looked beyond beatmatching when I judged DJing. When the Sync button came into existence, it didn’t phase me since I was already looking at other aspects when grading DJs.

Perhaps my biggest problem with beatmatching is that it is taken way too seriously. By now you should realize there is more to DJing than just beatmatching, yet too many people focus on just that aspect. People tend to overreact when beats get off even the slightest. I’ve heard mixes where the beats got off just a little for a fraction of a second, the DJ reached over and corrected it instantly, and yet some raver leans over and complains the DJ sucks. Some people will accuse a DJing of trainwrecking the second they hear the beats drift apart. They always assume the DJ must lack skill for allowing that to happen, and you’ll often hear someone brag about their buddy who is so skilled they can beatmatch perfectly for hours or the entire length of a track without touching the decks. Skill is only part of the equation, and we’ll examine why when I discuss unfair comparisons.

Beatmatching involves adjusting tempos. Should we really be focusing our attention on just that? Should that be the criterion that determines whether someone can get booked or not? Should we really be making such a big deal over the Sync button?

Common Wrong Conclusions

Every single time I complain about people taking beatmatching way too seriously, I encounter the same wrong conclusions. So let us take care of these right away. Obviously, the first thing they assume is that I do not know how to beatmatch. Then they assume I am against beatmatching. They always follow that up with “Do you want to hear DJs trainwreck?”

For now, let us skip to the second wrong conclusion. Am I anti-beatmatching? No. I prefer beatmatching, but I’ll take quality music over beatmatching any day. If I had to choose between cheesy Top-40 tracks beatmatched, or quality underground tracks unmixed, I’ll choose the quality underground tracks. Think of how many non-electronic albums you may own that are not mixed. Does that prevent you from enjoying them? Think of all the concerts were artists play their songs without blending them into one another. Does that ruin the experience? Think about the DJs who do annoying rewinds, which completely defeats the purpose of beatmatching, and yet the audience cheers them on. When I first got into electronic music, I preferred unmixed CDs. I wanted to hear the tracks as the artist originally created them.

Since they assume that I am against beatmatching, they always follow that up by assuming I want to hear DJs trainwreck. I do not want to hear DJs trainwreck. Trainwrecking occurs when someone tries to beatmatch, and for some reason fails to do so. It could be a lack of skill or it could be technical difficulties. If a DJ cannot beatmatch, then they shouldn’t try. Think of how many wedding DJs and radio DJs play music without beatmatching. In some cases, they will do short fades between songs to avoid the silence between tracks. Do you hear trainwrecking? No, because they are not attempting long mixes. I will respect a DJ more if they play tracks back to back than if they try to beatmatch and can’t.

When it comes to the Sync button, the argument isn’t whether you should beatmatch or not. It’s whether you should beatmatch manually or not. Using the Sync button still involves beatmatching. When a person makes the statement that they don’t care if a person knows how to beatmatch, what they mean is that they don’t care if the person knows how to beatmatch manually. It doesn’t mean they are against beatmatching and it doesn’t mean they want to hear someone trainwreck.

My Mixing Experience

With those two wrong conclusions addressed, it’s time to return to the first one. Can I beatmatch? I started DJing when vinyl ruled supreme. I was a music junkie, and most of the tunes I could only acquire on vinyl. Mixing on CDs didn’t become accepted until Pioneer released the CDJ-1000, and even then mixing on CDs stirred up controversy. It’s almost hard to believe there was a time when CD DJs were called fakes. The Sync controversy is basically history repeating itself.

I started mixing before the CDJ-1000 was released. The king of all vinyl turntables was the Technic 1200s, but I chose a different route. I decided that if I could mix on cheap tables, I could mix on anything. My friend was selling a used set of vintage Technics tables. I believe they were the SL-D2. The pitch was controlled by turning a dial instead of using a fader. I taught myself how to mix on them. The tables were fairly weak, and soon they were holding me back. That same friend later sold me his Gemini PT-2000s. At the time, I believed they were just generic Technics with no difference. I mixed on them for months before I ever touched the 1200s. The first time I mixed on 1200s, I was blown away at how powerful the torque was. I could match tempos in half the time. It almost felt as if the tables beatmatched for me. I now understood why they were so popular.

When I felt confident enough to mix out, I decided to invest in some real tables. The Numark TTX1 tables had just been released, and the reviews were phenomenal. I bought a pair and fell in love. My friends had a hard time believing me when I said they were better than Technics. I couldn’t vouch for reliability, only time will tell, but the powerful torque made beatmatching even easier than on Technics.

The first step in the beatmatching process is knowing when to start mixing. Timing is an art form all of its own. I studied my favorite mix CDs and many of the big name DJs. They were able to capture the energy of each track by playing the best parts, and they could give chills just by having the next track drop in at the perfect moment. This became my goal. I began noticing that the average DJ just played a track the whole way through then faded into the next. Their beatmatching was flawless, but their mixing was boring.

I took pride in my timing, and I’d like to point something out. Imagine I’m mixing from track 1 into track 2. Track 2 has a 2 bar breakdown where I plan on fading track 1 out of. When the beat kicks back in, there are 8 bars before the vocal kicks in. Track 3 has an 8 bar intro before the bassline kicks in. If I start mixing track 3 in at precisely the moment the beat kicks in on track 2, then the vocal and bassline should drop simultaneously. There are a few things that make this difficult. First, I have to fade out track 1, load track 3, and find the down beat of track 3 all within 2 bars! Second, I only have 8 bars to beatmatch track 3. Now anyone who has been mixing for a long time can usually mix within a few bars. My goal is to fade it slowly in over those 8 bars. I have only one option, and that is to mix on the fly. Just about every DJ will consider mixing on the fly to be an act of both skill and courage. Unfortunately, when the audience hears any kind of tempo fluctuation, they assume the DJ is struggling and therefore lacking in skill. Do you see the problem? Now do you understand why I believe beatmatching is taken too seriously?

Another thing I loved about mixing, was finding two tracks that went perfectly together. In some case, two tracks would match each other so well, it was if they were meant to be together. Both tracks would embellish one another and create some kind of super track. I got addicted to layering tunes. I would mix the next track in only a few bars after the previous track was mixed in, then I would combine them for as long as possible. This would eventually lead to two problems. First, I would realize at some point that I needed to end one track to cue up the next since I only had two turntables available. Second, the two tracks enhanced each other so well, that ending one track would suck all the life out of the other track. I needed a solution to this problem.

After mixing on my Numark TTX1 tables for so long, I found I would lose my touch on Technics. At times, I would struggle up on stage and my mixing would suffer. So I invested in a single Technics table. I now had a three table setup at home, and I had a solution to my layering problem. I started mixing on three tables, and I realized that beatmatching wasn’t the hard part. The hard part was finding three tracks that went well together. I reorganized my records so all the repetitive tunes were kept together. I evolved a style where I would mix one track out while mixing another one in. I used the three table setup to constantly layer two tracks. I would beatmatch non-stop for over 30 minutes straight.

Put yourself in my shoes. I’m surrounded by DJs who primarily transition between two tracks on two turntables. The average DJ spends most of their time cuing up the next track and getting it ready. When it comes time to mix, their mix only lasts a minute or so. By contrast, I’m mixing on three tables, mixing on the fly, and beatmatching almost my entire set. I have to deal with these DJs bragging about how they don’t need the Sync button. If my mixing was that easy, I wouldn’t bother either. Also, how do you think I feel when people assume I can’t beatmatch because I think it is taken too seriously?

Unfair comparison

Imagine you’re at a club and there are four DJs mixing that night. The first DJ mixes flawlessly, the second mixes flawlessly, and the third mixes flawlessly. You can’t say the same for the fourth. There were a few moments throughout their set where the mixing got slightly off. They never trainwrecked, but their set was not flawless. The assumption most people would make is that that DJ must lack the skill that the other three DJs possessed. What if you actually studied all four DJs? You found the first three used two turntables, spent almost the entire length of each tracking cuing up the next one, and mixed for about a minute each. The fourth DJ mixed on three tables, mixed each track immediately on the fly, and layered tracks for most of their set. Would you believe the fourth DJ is less skilled than the first three?

I watched a YouTube video of the Purpose Maker Mix by Jeff Mills. His skill as an artist blew me away. The beatmatching wasn’t flawless, but it was live and raw. He was mixing on three tables and just throwing records on and off while mixing on the fly. His hands were flying all over the EQ and faders, and you could totally jam out to the mix. Sadly, I read comments from people bashing him for his rough mixes. Fortunately, most of the comments praised him for his skill and pointed out all the other factors that needed to be considered.

I get annoyed when people bash a DJ because their beatmatching isn’t flawless. In most cases, they are not taking into consideration all the facts. When it comes to skill, there are three things to consider. How long did they set up the mix? How long did they spend time mixing? How many turntables are they using? If the audience isn’t going to take these factors into account, then why should they care if someone uses the Sync button?

Additional factors

A DJ’s ability to beatmatch flawlessly isn’t just a matter of skill. There are technical issues one must consider as well. Does the tempo fluctuate? Was the track spliced together properly during production? Is there a phantom tempo during a beatless breakdown? What kind of tables are being used? How are the tables laid out and how far apart are they?

When I spun just vinyl, there were records that always gave me problems. I would struggle to beatmatch some of them. For some it was obvious that the tempo was not staying constant. It wasn’t until I recorded my records and applied a beatgrid over top them that the tempo fluctuations became visually obvious. Some tracks slowly sped up or slowed down, others moved all over the place. Some moved a little and some moved a lot.

In some cases, the tempo would remain constant, then suddenly get off and remain constant again. That tells me there was a sloppy splice during production. This also explains why when I was mixing perfectly it would just suddenly get off. The audience always assumes it is the DJ’s fault.

When a track fades to a beatless breakdown, be it an ambient breakdown or a vocal breakdown, there is this assumption that a phantom tempo is still keeping time. In most cases this is true, but not always. For some tracks the beat will kick back in completely off time. For transitional DJs who mix one track at a time, this may not be much of an issue. For a combination DJ who layers tracks, this is catastrophic. Again, the audience blames the DJ for lacking skill rather than assume it’s a poorly produced track.

On some occasions, I’ve shown up at venues to find the promoter is using a set of cheap tables. If you work the pitch fader alone, it takes forever for the tempo to catch up. If you touch the platter the slightest, it comes to a dead stop. If you give the platter the slightest nudge, it overspins. For a transitional DJ, this is a minor inconvenience. Many of them will just take longer cuing up their tracks and will shorten their transitions. For a combination DJ, this ruins their style. It becomes plainly obviously that I won’t be mixing on the fly and I should avoid long mixes when I encounter these situations.

I remained a vinyl DJ long after CDs took over. The newer 4 channel mixers started only having 2 analog inputs. I would do three turntable mixes where I would use two vinyl tables and one CDJ. Most promoters would lay their tables out with the CDJs on the inside and the vinyl tables on the outside. This meant my primary tables were far apart. For a transitional DJ, this is a minor inconvenience. For a combination DJ, this was a major pain. But it gets much worse. To complicate matters, the table layout didn’t match the mixer layout. Some promoters would use channels 1 & 2 for vinyl and 3 & 4 for CDs. So while the table layout was vinyl, CD, CD, vinyl; the mixer layout was vinyl, vinyl, CD, CD. In other words, deck 2 was deck 3, deck 3 was deck 4, and deck 4 was deck 2. Do you have any idea how hard it is to mix under those conditions? On one occasion, I had to deal with that setup and the cheap tables I mentioned in the previous paragraph!

I’m surrounded by two turntable transitional DJs. They don’t see things the way I do. The mixer layout not matching the table layout doesn’t bother them since they are only mixing on two tables and doing short transitions. I end up coming off as the annoying DJ who is always complaining.

Advanced Perspective

It’s easy to say beatmatching involves matching tempos, and it’s easy to see how that is physically achieved, but what goes through the DJ’s mind? Let’s look at beatmatching from an advanced perspective. As a multi-genre DJ, my mixing style varies. I prefer three table combination mixing, but it does not work for all styles. It’s easy to layer instrumental tracks, but not so much vocal tracks. As a result, my beatmatching techniques vary whether I’m doing a short transition, a long combination on two tables, or a combination on three tables. I’d like to share with you how these differ.

First, let’s look at the two ways you can adjust the pitch. A DJ can rely on the pitch fader alone, or they can use the pitch fader and make small touches to the platter. Relying on the pitch fader takes longer and is much more difficult. It requires more skill. Touching the platter is faster and easier, but can lead to some problems. I mentioned earlier that cheap turntables can stop or overspin when you touch the platter. Even powerful tables can spring forward or back a bit. Also, changes in pitch are more audible when you touch the platter. I’ve heard some argue that real DJs should never touch the platter for beatmatching. I use both methods depending on the situation.

There are a few rules that DJs learn that determine which table should be adjusted. If the incoming table is maxed out, then the currently playing table may need to be adjusted. If one track is a vocal track, then that track should not be touched since changes in pitch are easier to hear in vocals (assuming the DJ is not using key correction). If you are going to touch the platter, experience will teach you to do so between words. Changes in pitch are extremely noticeable in lush, melodic tunes with long sustained pads. Trance and progressive house tunes often fit into this category. Dramatic changes in pitch to these tunes should be avoided, and if necessary, rely on the pitch fader alone. Also, avoid mixing on the fly if changes in pitch are very noticeable. For all other tunes, the rules vary per style.

The two turntable transitional style of beatmatching is the easiest. Part of what makes it so easy is that there is clearly a primary and secondary track. The currently playing track is the one that has everyone’s attention and therefore becomes the primary track. The track being mixed in is the secondary track and must match the tempo of the primary. Since the transition is short, it is easy to tell the two apart. Any adjustments to the tempo are done on the secondary track, and in what direction is usually easy to figure out. Changes in the music, such as filter sweeps and breakdowns, can making transitioning easier. At some point, the audience’s attention is shifted to the incoming track. When this happens, the incoming track becomes the primary track. The outgoing track is now secondary, and any tempo changes should be done at that track.

Things become more difficult during long, layered mixes. At some point the tracks combine into an enhanced super track. No single track has their attention. When the beats drift off, which track do you adjust? Do you slow the faster track, or do you speed up the slower track? Making things more difficult is the fact that since the tracks melted together, it becomes difficult knowing which track is which. You may notice the hi-hats are off, but which hi-hat belongs to which track? The solution to this problem is actually quite easy. You guess. What I’ll do is give one track an extremely slight nudge. Within a fraction of a second, I’ll determine if the mix got better or worse. If it got better then I went the right direction, if it got worse then I’ll fix it instantly.

For the two turntable transitional style of mixing, it is easy to know which track to adjust and in which direction. For the two turntable combination style of mixing, it is difficult to choose which to adjust and in what direction, but it is easy to just guess and fix it. The rules of beatmatching change when you involve a third table. Most DJs don’t use three table setups, and are not aware of this. Like the two table combination style, all three tracks can melt into one, but what differs is the fact that you cannot rely on guessing which one to fix. If one table gets off, you cannot guess or you may end up with all three tracks off. You have to identify the problem track by process of elimination. To do this, you cue up two tracks at a time in your headphones. You determine which tracks are locked together, and which track is off. This can take a few seconds, but up on stage that is a long time. The longer it takes to determine which of the three tunes is off, the more the audience will lose respect for you. They expect you to be just as flawless as the two turntable transitional DJs.

Now consider all the factors I mentioned earlier. Imagine doing a three table mix and one record does not have a steady tempo. Imagine one of the three records has a bad splice, and suddenly your are trainwrecking on stage, but you can’t just guess, you have to identify which of the three it is. Now imagine the promoter has the layout on the mixer different than the layout of the tables. Now you know what I deal with.

Beatmatching is a balancing act; it’s like trying to mix while standing on one foot. Using the Sync button is like being able to stand on two feet. You don’t have to worry about cheap turntables, you don’t have to worry about tempo fluctuations, and you don’t have to worry about bad splices. You can just enjoy mixing. It doesn’t mix for you. You still have to find the music, you still have to determine which track to play, and you still have to determine where you will mix in and mix out. You still get to be creative with your fades, your EQing, your looping, and your effects. With the Sync button, you can relax and focus more on those things. You’d be surprised at how much more fun DJing can become.

Why do you DJ?

Let’s take a moment to look at the videogame world. Some people like to play games on the hardest difficulty, while others want to just breeze through the game. Some people love the single player experience, while others only play multiplayer. Some people try to complete every task, while others just want to finish the game. When it comes to a game like Grand Theft Auto, some people try to complete every main mission, every side mission, and find every hidden package. Others love just running around aimlessly causing havoc. The point I’m making is that there is no wrong way to play videogames as long as you are having fun. I feel the same is true about DJing. No one can tell you how to mix, because there is no right way to mix.

Every DJ likes to brag about how they are in it for the music, but actions speak louder than words. If you are in it for the music, then focus on that. I’ve already written an article about different kinds of DJs, so I won’t go into too much detail here. There are many reasons why people become DJs, but I doubt anyone became a DJ for the purpose of adjusting tempos.

When it comes to cooking, there are many skills involved. A skilled cook will have knowledge of various ingredients including herbs and spices. They’ll know which ingredients mix well together. They’ll know how much to add, and when to add them. They’ll also know how long to cook. All that knowledge is wasted if the food is burnt or undercooked. If a person told you they love cooking, but hated peeling potatoes or peeling onions, would you discredit all those other skills? Would you look at them confused and say that doesn’t make any sense? Beatmatching is just one small step in the whole mixing process, and automating that one process doesn’t discredit all the other skills. Stop calling it beatmatching, and start calling it “adjusting tempos”, and you’ll start to grasp what exactly it is.

How many people become cooks because they love to peel potatoes or peel onions? Did you become a DJ to adjust tempos? I doubt it. I enjoy beatmatching but I also enjoy using the Sync button. I get a total rush off beatmatching three decks, but I also love how relaxing it is to use the Sync button. Whether I choose to beatmatch manually or automate the process doesn’t really matter to me, because it has nothing to do with why I DJ. I love finding music, and I love sharing it. I love hearing how two tracks sound together. I love telling a story with my music. I love timing tracks in such a manner so as to give chills. I love being creative with my fading, my EQing, my effects, and my looping. When I use the Sync button, I can focus on those things more.

Reasons to Sync

I never got into CD DJing; I went from vinyl to Traktor control vinyl. I know how to mix on CDJs and own one for practice. I bought Traktor in 2010 since they bragged that you could mix 4 tables. I was disappointed to discover you could only use 2 control records or CDs, you could not mix and match them, and you could only mix on 4 internal decks if you used Sync. I had no desire to use the Sync button and didn’t own a controller. I beatgridded all my tracks so I could take advantage of loops and timed effects. Then one day, I had finished mixing and was about to turn off Traktor, when I decided to try the Sync button. Even though I was home alone, I actually looked around to make sure no one was watching. I was shocked to discover how much fun it was, but told myself I wouldn’t use it out. I still beatmatched with my tables, but I started using the Sync button when I wasn’t near my tables. I would mix in bed, on the couch, at the kitchen table, and one time I mixed on my lunch break. I loved being able to mix everywhere. Eventually, I would embrace the Sync button.

There are multiple reasons why you should embrace the Sync button. I’ve already pointed out that you can overcome the limitations of cheap turntables. It’s not uncommon for a venue to have a 4-channel mixer with only two decks. By using the internal decks, you can overcome the two table limitation. If you are using a controller, you don’t have to worry about the decks not matching the mixer layout.

One of the greatest advantages to the mixing process is the ability to beatmatch even when there aren’t any beats. Some tracks may have a spoken word introduction or feature ambient noises before the beats kick in. By utilizing the beatgrid and a beat counter, you can still mix the track in and the beat will kick in at the perfect moment.

Perhaps my favorite reason to embrace the Sync button is that it offers me the ability to practice everywhere. I once told a friend this and he was confused. He asked me how do I practice when it is beatmatching for me. My practice no longer has anything to do with beatmatching. When I practice, I study the structure of the tune, I test out how well it mixes with other tracks, and I make notes of where the best spots to mix in and mix out of are. With the Sync button, I can mix in bed, on the couch, at the kitchen table, and even during my lunch break at work. I love it!

One huge reason to embrace the Sync button is that it is actually fun. Again, why do you DJ? Did you become a DJ to adjust tempos and balance tracks? When I first used the Sync button, I was surprised how much fun I had. I loved how I could focus on the mixer more. I still occasionally mix vinyl, and I do get a rush off of beatmatching three tables, but there is something so relaxing about not dealing with having to balance tracks on one another. It’s like being able to stand on two feet after you’ve been mixing on one foot for years. If a person loves cooking but hates peeling potatoes, and someone invents a machine that automatically peels potatoes, then the person can enjoy cooking more. Mixing can be more fun when you use the Sync.

Problems with beatmatching

Beatmatching brings with it some problems. The first problem is that you need beats or at least some kind of tempo indicator. As I just stated, with the Sync button you can mix even before the beat kicks in. This was never possible with vinyl or CD.

Another problem with beatmatching is that people limit themselves to tracks that are within a certain tempo range. House DJs may not mix Drum & Bass because the tempos are too fast. Now this isn’t necessarily something the Sync button solves, but it does come down to us taking beatmatching too seriously. You don’t have to beatmatch every transition. Try stopping a tune and going into something with a radically different tempo. Don’t let a tune’s tempo prevent you from playing it. I used to do 4 hour sets where I would beatmatch almost the entire time. For the last 15 minutes of my set I would just start playing random tracks unmixed. The audience loved it.

One more problem with beatmatching is that it takes time. Even if you can beatmatch within two bars, that is still two bars that will prevent you from slamming it in. With the Sync button, I can cue up the next tune and drop it on beat. I’ve actually become very impatient when I go back to beatmatching on vinyl.

DJ Hypocrisy

If you study the history of DJing, you’ll realize just how hypocritical we are when it comes to complaining about the Sync button and calling users fakes. I mentioned earlier that CD DJs used to be called fakes during the 90’s, and there was great controversy when they became popular. Now we’ve got CD DJs calling laptop DJs fake. You would think they’d show a little consideration.

Disco DJs of the 1970’s realized that many tunes didn’t work well on the dancefloor. The earliest remixes involved restructuring the tracks so they worked better and allowed people to dance longer. As beatmatching became more and more popular, the music structure changed to accommodate that style of mixing. The intros and outros got longer, and many of them used an even number of bars consisting of 16 to 32 beats.

Electronic music brought quantization resulting in perfect tempos. The fluctuating tempo of a human drummer was no longer a problem. Newer digital audio workstations can even fix the fluctuations of human drummers through timestretching techniques.

Belt-driven turntables were replaced with powerful torque direct-drive turntables that made beatmatching easier. The first time I spun on the 1200s I was blown away by how easy it was to beatmatch on them.

Put it all together. We’ve restructured the music to make beatmatching easier, we’ve used quantization to make beatmatching easier, and we’ve relied on powerful turntables to make beatmatching easier. What right do we have to condemn people who use the Sync button? If you want to challenge yourself, then mix old funk and disco records on a belt-driven table. Then we’ll see just how perfect your beatmatching is.

What DJs complain

In this section I’ll discuss some of the complaints DJ lodge against the Sync button, and in the next section I’ll explain why they complain. One of the complaints is that using the Sync button makes DJing too easy. There are two problems with this complaint. First, many of these DJs are two turntable transitional DJs. They are already mixing at the most pathetically, simplistic style of mixing and can’t imagine making it any easier. Many of these DJs only transition for a minute or so. They have a limited perspective of DJing, and don’t take the time to consider the harder styles of mixing. Remember the person carrying the buckets who thinks he is doing more work simply because he focuses on the physical aspect? He fails to acknowledge that he is carrying less and getting less done. You can have a DJ mixing on two tables thinking he is doing more work than a person on four decks simply because he is manually beatmatching. The second problem with this complaint is that some DJs do not care about the challenge. They mix because they love finding and sharing music. They mix because they love hearing how two tunes can join together into one. They do not DJ for the purpose of adjusting and balancing tempos.

I’ve heard some DJs complain that people who use the Sync button are afraid of trainwrecking. They call them cowards and tell them to just accept that trainwrecks may happen whether or not it’s the DJ’s fault. For example, someone may bump the table while you’re mixing vinyl and the needle skips causing you to trainwreck. This is DEFINITELY the mindset of a transitional DJ. A transitional DJ’s goal is to transition from track A to track B. If they start trainwrecking and can’t fix it, then they’ll just cut over to track B. The mix may not have been as elegant as they intended, but their goal was still achieved. If your goal is to combine two tracks, then trainwrecking will destroy that goal. Trainwrecking is a minor inconvenience for transitional DJs, but catastrophic for combination DJs. Not only is your goal ruined, but stopping one track can suck all the life out of the remaining track.

The most common complaint is that now anyone can be a DJ. If you consider all the different skills involved in DJing, then this excuse just becomes lame. If a DJ can beatmatch flawlessly and still suck, then the Sync button won’t change a thing. The problem is not the Sync button, the problem is the low standards we have for DJs. Blame the promoter not the Sync button.

Finally, many DJs complain that the Sync button isn’t reliable. You’ll hear stories of DJs who used the Sync button and still trainwrecked. The Sync button is extremely reliable if you take the time to prepare your music properly. I use Logic to fix any tempo fluctuations and bad splices in my collection. I skip through every track and adjust the beatgrid so it is perfect. The DJ scene is full of lazy DJs. Many DJs just want to mix without taking the time to prepare their tracks properly. It’s disturbing how many Serato and Traktor DJs I know of who don’t set load points, cue points, loops, or proper beatgrids on their collection. They want to mix their digital files as if they were still mixing vinyl. When these DJs test out the Sync button, it doesn’t work for them.

Why DJs complain

Why do so many DJs complain about the Sync button? For most, it is an ego thing. The bigger the ego, the more stubborn to change. Many DJs will look for any excuse to brag.

I think the really sad part is that for most DJs being able to beatmatch is their only skill. They don’t know how to time their music to perfection, and they don’t know how to tell a story with their music. They just beatmatch one track into the next. These DJs don’t like the idea that they can be replaced with a button. They call the Sync button DJs cowards when in fact they are the cowards.

The biggest reason they complain is because the Sync button exploits the initiation rite of learning how to beatmatch manually. They fear anyone can be a DJ now. I cannot stress enough the need for higher DJ standards. If we judged DJs on the quality of their music, the variety of their music, their ability to read and work the crowd, their ability to tell a story with their music, their ability to time their mixes perfectly, and their creativity with the mixer, then the Sync button wouldn’t be an issue.

Should you learn to beatmatch?

I don’t really have a definite answer to this question. Should a person learn how to race a horse before learning how to race a car? Should a person learn Morse code before learning how to use a phone? Should a person learn how to use an abacus before learning how to use a calculator? Should a person learn how to paint with oil before using Photoshop? Should a person play PS1 or Atari 2600 before buying a PS4? Have I made my point?

I often hear people say “What if you show up at a venue and you can only use CDs or vinyl”? If I show up at a venue with vinyl and they only have CD decks, then I probably won’t mix that day. If I show up at a venue with CDs and they are doing an all vinyl night, I probably won’t mix that day. If you started out as a laptop DJ, and they won’t let you use your laptop, they you just won’t mix that day. I have a vinyl collection because of when I started mixing, but I wouldn’t bother with it if I were starting out now. If I were a new DJ and someone was throwing an all vinyl night, I just wouldn’t mix there. People act like learning how to beatmatch can be a life or death skill. They act as if someone is going to put a gun to your head and ask you to beatmatch.

I will say this on the matter, if you truly love something then you should try to learn as much as you can about it. Don’t limit yourself. Beatmatching can be fun at times. Digital technology has allowed me to jump all over tunes. Vinyl is very linear. My mixing is different with vinyl than with digital. As a result, I have actually learned different techniques because of vinyl. Vinyl forces me to be more creative in some ways. It has a different feel, and it is both challenging and fun. So embrace the Sync button, but don’t be afraid to learn how to beatmatch.

Click here to return to the top